Latest genomic technology uncovers secrets of immune system's response to malaria

Scientists have revealed for the first time how immature mouse immune cells, called T cells, choose which type of skills they will develop to fight malaria infection. Reported today (3 March) in Science Immunology, researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, European Bioinformatics Institute and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Australia, tracked individual T cells during infection with malaria parasites. They discovered a whole network of chemical conversations between different types of cells that influenced T cell specialisation.

Using the latest single-cell genomics technology and computational modelling, the study also discovered genes within the T cells that may be involved in controlling antibody production during malaria infection. One of these, Galectin 1, encouraged development of a particular type of T cell when active. These genes are possible drug targets to boost immunity to malaria and other infections.

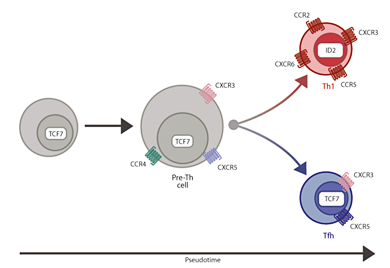

The immune system is extremely complex and responds to disease by developing specific types of immune cells. Two different types of T cell – T helper1 (Th1) and T follicular helper (Tfh) – develop and help fight infection. The researchers discovered that more Th1 cells were produced when a gene called Galectin 1 was active. These Th1 cells help remove parasites from the bloodstream and are needed early on in an infection, however for longer-term immunity, more Tfh cells are needed.

“This is the first time that Galectin 1 acting inside T cells has been seen to influence Th1 fate, and has shown that Galectin 1 is a possible therapeutic target for malaria. An important next step will be to test many of the new gene targets identified by our studies, to see if they can be targeted by drugs to boost immunity to malaria.”

Dr Ashraful Haque Joint lead author from the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia

The exact molecules that encourage the T cells to develop into one or the other form are poorly understood. The researchers used single-cell RNA sequencing to take ‘snapshots’ of the active genes produced by each individual T cell after the mouse was infected with malaria. With these snapshots of data, the researchers identified all the different stages between immature T cells and fully specialised Th1 or Tfh cells.

“This is the first high-resolution time-course of cells using a pathogen in mice, where we have used cutting edge genomics coupled with computational methods to reconstruct how cells evolve and develop over infection. With methods from machine learning, we have simplified really complex biological processes into something we can understand. This approach could be applied to resolve any biological developmental process.”

Dr Sarah Teichmann Head of Cellular Genetics at the Sanger Institute and joint lead author on the paper

The team also developed a new computer modelling system called GPfates* which allowed them to see how all the cells related to each other. This uses methods from spatio-temporal statistics, to show which genes were switched on in each of the two distinct cell states (Th1 and Tfh).

“Using genomics we uncovered the inter-cellular conversation that is taking place between immune cells such as monocytes and Th1 cells. This has not been seen before, and our data have allowed us to uncover tens or hundreds of new genes that may be involved in controlling the production of antibodies. Activity in these genes may help the body, for example in curing an infection, or may hinder by allowing cancerous cells to flourish. The principles and the computational methods we have developed here could be applied to future studies to explore these questions.”

Dr Oliver Stegle Joint lead author from the European Bioinformatics Institute

More information

About the methods:

* GPfates modelling system was developed for characterizing cell differentiation toward multiple fates. The software framework that underlies this machine learning method was first developed by computer scientists in Sheffield to enable the flexible implementation of a variety of different models. The researchers adapted and applied it into GPfates for single cell RNA data analysis.

GPfates and a database, www.PlasmoTH.org, which facilitates discovery of novel factors controlling TH1/TFH fate commitment are available for other scientists to use.

Funding:

This work was supported by Wellcome (no. WT098051), European Research Council grant ThSWITCH (no. 260507), Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Project grant (number 1028641), and Career Development Fellowship (no. 1028643), University of Queensland; Australian Infectious Diseases Research Centre grants; and the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine. Further support was provided by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Australia andOzEMalaR, the Lundbeck Foundation and the Marie Curie Innovative Training Networks grant “Machine Learning for PersonalizedMedicine” (EU FP7-PEOPLE Project Ref 316861, MLPM2012).

Participating centres:

- European Molecular Biology Laboratory, European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, U.K.

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, U.K.

- QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Herston, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- Department of Microbiology andImmunology, Peter Doherty Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

- Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, U.K.

- National Health Service Blood and Transplant, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Long Road, Cambridge, U.K.

- Department of Computer Science, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, U.K.

- Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Advanced Molecular Imaging, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Publications:

Selected websites

QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute

QIMR Berghofer is a world-leading medical research institute in Brisbane, Australia. Its research is focused on cancer, infectious diseases, mental health and chronic disorders. QIMR Berghofer has established an international reputation for research excellence and consistently rates in Australia’s top two medical research institutes.

European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI)

The European Bioinformatics Institute is part of EMBL, and is a global leader in the storage, analysis and dissemination of large biological datasets. EMBL-EBI helps scientists realise the potential of ‘big data’ by enhancing their ability to exploit complex information to make discoveries that benefit mankind. We are a non-profit, intergovernmental organisation funded by EMBL’s 21 member states and two associate member states. Our 570 staff hail from 57 countries, and we welcome a regular stream of visiting scientists throughout the year. We are located on the Wellcome Genome Campus in Hinxton, Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive. We’re a global charitable foundation, both politically and financially independent. We support scientists and researchers, take on big problems, fuel imaginations and spark debate.