Early skeleton map reveals how bones form in humans

Listen to “Early skeleton map reveals how bones form in humans” on Spreaker.

The first ‘blueprint’ of human skeletal development reveals how the skeleton forms, shedding light on the process of arthritis, and highlighting cells involved in conditions that affect skull and bone growth.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and collaborators have used cutting-edge genomic techniques to identify all the cells and pathways involved in the early stages of skeletal development. Part of the wider Human Cell Atlas project,1 this resource could be used to investigate whether current or future therapeutic drugs could disrupt skeletal growth if used during pregnancy.

The study, published today (20 November) in Nature, shows a clear picture of how cartilage acts as a scaffold for bone development across the skeleton, apart from the top of the skull. The team mapped all the cells critical for skull formation and investigated how genetic mutations may cause soft spots in the skull of newborns to fuse too early, restricting the growth of the developing brain. In the future, these cells could be used as possible diagnostic and therapeutic targets for identifying and treating congenital conditions.

They also found certain genes activated in early bone cells that might be linked to an increased risk of developing hip arthritis as an adult. Comparatively, they suggest that other genes in early cartilage cells are linked to an increased risk of developing arthritis in the knee, possibly due to their role in cartilage repair. In the future, studying these different cells further could help develop new treatments for these conditions.

Overall, the developing skeletal atlas is a freely available resource that can be used to understand more about bone development and how this influences conditions affecting these tissues that occur in children and adults.

This paper is one of a collection of more than 40 Human Cell Atlas publications in Nature Portfolio journals that represent a milestone leap in our understanding of the human body. These highly complementary studies have shed light on central aspects of human development, and health and disease biology, and have led to the development of vital analytical tools and technologies, all of which will contribute to the creation of the Human Cell Atlas.1

Children’s skulls fully harden and fuse when they are between the ages of one and two years old. Before this developmental process, there are soft spots in the skull that allow the brain to continue to grow after the child is born. In some cases, these soft spots fuse too early, causing a condition known as craniosynostosis, which prevents the brain from expanding.

In the UK, this is usually treated quickly via an operation but if left untreated, it can cause a build-up of pressure in the skull, leading to learning difficulties, problems with sight, and hearing loss.2 While craniosynostosis has been linked to genetic mutations, it has not been possible until now to identify which cells in humans these mutations disrupt.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in the UK and causes joints, such as the hip and knees, to become painful and stiff over time.3 This is because the protective layer, known as cartilage, around these joints has become broken or worn down.3 Eventually, in most cases, it is necessary to replace the joint through major surgery, as adults cannot grow new cells to repair the damaged cartilage.

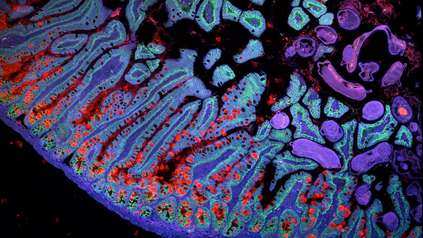

Using new cutting-edge technology,4 researchers from the Sanger Institute and collaborators mapped skeletal development in the first trimester of pregnancy, from 5 to 11 weeks post-conception,5 at a spatial and single-cell levels.6 This enabled them to describe all the cells, gene networks, and interactions involved with bone growth during early development, including the position of cells in the rapidly growing tissue.

A 3D view of rendered images showing a developing cranium, where the cartilage is blue and the bone is shown in purple. In this image, the top of the skull does not have any cartilage (blue), showing it forms bone (purple) uniquely without needing cartilage. [Video kindly provided by: A.Chédotal & R. Blain, Institut de la Vision, Paris & MeLiS/UCBL/ HCL, Lyon]

The single-cell map revealed how cartilage cells grow first, acting as a scaffold for bone cells to then grow over. The team highlighted how this happens everywhere in the skeleton apart from the top of the skull, called the calvarium. Within the calvarium, they discovered new types of early bone cells that are involved in skull development. The team investigated how genetic mutations that are linked with craniosynostosis disrupt these early bone cells, causing them to fuse too early.

The researchers also found that genetic variants associated with a higher risk of hip osteoarthritis were involved in early bone cell development and their downstream regulators, while variants that affected knee arthritis risk were involved with cartilage formation.

Additionally, the team used the atlas to explore the impact of medication on skeletal development. They compiled a list of 65 clinically-approved drugs, that are currently not recommended during pregnancy, and highlighted where these may disrupt skeletal development. By including this information in the atlas, it highlights the impact drugs can have on the developing human and could be informative when considering whether therapeutics are safe for use during pregnancy.

“There are countless processes that act in concert during human skeleton and joint development, and our research has characterised cell types and mechanisms involved in the formation of bone and the fusing of the skull. By studying these, we were able to give context to DNA variants linked with congenital conditions, such as craniosynostosis, predicting how genetic changes impact the developing skeleton. Ultimately, using this atlas could help us better understand the conditions of both the young and ageing skeleton. Having this ‘blueprint’ of bone formation can also help us develop effective ways to grow bone and cartilage cells in a dish, which has enormous therapeutic potential.”

Dr Ken To, co-first author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“We’re excited to have created the first multi-omic map of the developing human skeleton, something that has vast potential in both understanding how our bones grow and treating conditions that might impact this. Our multi-layered, time- and space-resolved atlas enabled novel computational analyses, which we used to create an integrated view of how developmental processes are regulated. Having a clearer picture of what is happening as our skeleton forms, and how this impacts conditions such as osteoarthritis, could help unlock new treatments in the future.”

Dr Jan Patrick Pett, co-first author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“Our unique freely available skeletal atlas sheds new light on cartilage, bone, and joint development in the first trimester, detailing the cells and pathways involved together for the first time. This atlas combines cutting-edge spatial technology with genetic analysis and can be used by the research community worldwide. This detailed atlas of bone development in space and time is coordinated with other studies which brings the entire Human Cell Atlas initiative one step closer to fully understanding what happens in the human body across development, health, and disease.”

Professor Sarah Teichmann, co-founder of the Human Cell Atlas and senior author previously at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, now based at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute at the University of Cambridge

More information

The freely available human skeletal atlas can be found here:

https://developmental.cellatlas.io/skeleton-development

- This study is part of the international Human Cell Atlas (HCA) consortium, which is creating comprehensive reference maps of all human cells as a basis for both understanding human health and diagnosing, monitoring, and treating disease. The HCA is an international collaborative consortium whose mission is to create comprehensive reference maps of all human cells—the fundamental units of life—as a basis for understanding human health and for diagnosing, monitoring, and treating disease. The HCA community is producing high-quality Atlases of tissues, organs and systems, to create a milestone Atlas of the human body. More than 3,500 HCA members from over 100 countries are working together to achieve a diverse and accessible Atlas to benefit humanity across the world. Discoveries are already informing medical applications from diagnoses to drug discovery, and the Human Cell Atlas will impact every aspect of biology and healthcare, ultimately leading to a new era of precision medicine. https://www.humancellatlas.org

- Craniosynostosis, NHS. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/craniosynostosis/

- Osteoarthritis, NHS. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoarthritis/

- This atlas combined spatial transcriptomics with single-nuclei transcriptional and epigenetic profiling of 336,000 nucleus droplets. The researchers developed ISS-Patcher, a new tool that can impute cell labels from the droplet data and transfer it to the high-resolution sequencing datasets. This gives information on all the cells present in a sample, where they are, and how they interact with the environment around them. They also used a new spatial transcriptomics annotation tool, called OrganAxis, to map the trajectory of the developing cranial bone.

- The researchers analysed human embryonic limb and cranial tissues between weeks 5 to 11 post-conception, provided by the INSERM biobank in France and the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University of Cambridge.

- The team paired multiple spatial transcriptomics methods with RNA and DNA sequencing to decipher the gene regulatory networks that are involved in bone and joint formation across space and time, mapping how cell linages develop.

Publication:

To, L. Fei, J. P. Pett, et al. (2024) A multiomic atlas of human early skeletal development. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08189-z

Funding:

This work was funded in part by Wellcome, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and the Medical Research Council. A full acknowledgement list can be found on the publication.