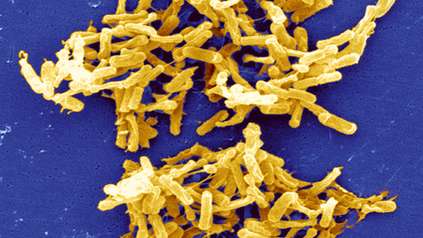

Diarrhoea-causing bacteria adapted to spread in hospitals

Scientists have discovered that the gut-infecting bacterium Clostridium difficile is evolving into two separate species, with one group highly adapted to spread in hospitals. Researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and collaborators identified genetic changes in the newly-emerging species that allow it to thrive on the Western sugar-rich diet, evade common hospital disinfectants and spread easily. Able to cause debilitating diarrhoea, they estimated this emerging species started to appear thousands of years ago, and accounts for over two thirds of healthcare C. difficile infections.

Published in Nature Genetics today (12 August), the largest ever genomic study of C. difficile shows how bacteria can evolve into a new species, and demonstrates that C. difficile is continuing to evolve in response to human behaviour. The results could help inform patient diet and infection control in hospitals.

C. difficile bacteria can infect the gut and are the leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea worldwide*. While someone is healthy and not taking antibiotics, millions of ‘good’ bacteria in the gut keep the C. difficile under control. However, antibiotics wipe out the normal gut bacteria, leaving the patient vulnerable to C. difficile infection in the gut. This is then difficult to treat and can cause bowel inflammation and severe diarrhoea.

Often found in hospital environments, C. difficile forms resistant spores that allow it to remain on surfaces and spread easily between people, making it a significant burden on the healthcare system.

To understand how this bacterium is evolving, researchers collected and cultured 906 strains of C. difficile isolated from humans, animals, such as dogs, pigs and horses, and the environment. By sequencing the DNA of each strain, and comparing and analysing all the genomes, the researchers discovered that C. difficile is currently evolving into two separate species.

“Our large-scale genetic analysis allowed us to discover that C. difficile is currently forming a new species with one group specialised to spread in hospital environments. This emerging species has existed for thousands of years, but this is the first time anyone has studied C. difficile genomes in this way to identify it. This particular bacteria was primed to take advantage of modern healthcare practices and human diets, before hospitals even existed.”

Dr Nitin Kumar Joint first author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

The researchers found that this emerging species, named C. difficile clade A, made up approximately 70 per cent of the samples from hospital patients. It had changes in genes that metabolise simple sugars, so the researchers then studied C. difficile in mice**, and found that the newly emerging strains colonised mice better when their diet was enriched with sugar. It had also evolved differences in the genes involved in forming spores, giving much greater resistance to common hospital disinfectants. These changes allow it to spread more easily in healthcare environments.

Dating analysis revealed that while C. difficile Clade A first appeared about 76,000 years ago, the number of different strains of this started to increase at the end of the 16th Century, before the founding of modern hospitals. This group has since thrived in hospital settings with many strains that keep adapting and evolving.

“Our study provides genome and laboratory based evidence that human lifestyles can drive bacteria to form new species so they can spread more effectively. We show that strains of C. difficile bacteria have continued to evolve in response to modern diets and healthcare systems and reveal that focusing on diet and looking for new disinfectants could help in the fight against this bacteria.”

Dr Trevor Lawley The senior author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

“This largest ever collection and analysis of C. difficile whole genomes, from 33 countries worldwide, gives us a whole new understanding of bacterial evolution. It reveals the importance of genomic surveillance of bacteria. Ultimately, this could help understand how other dangerous pathogens evolve by adapting to changes in human lifestyles and healthcare regimes which could then inform healthcare policies.”

Prof Brendan Wren An author from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

More information

Publication

Nitin Kumar and Hilary Browne et al. (2019) Adaptation of Host Transmission Cycle During Clostridium difficile Speciation. Nature Genetics DOI: 10.1038/s41588-019-0478-8

More information on C. difficile bacteria

C. difficile bacteria are found in the digestive system of about 1 in every 30 healthy adults. The bacteria often live harmlessly because other bacteria normally found in the bowel keep it under control. But some antibiotics can interfere with the balance of bacteria in the bowel, which can cause the C. difficile bacteria to multiply and produce toxins that make the person ill.

Once out of the body, the bacteria turn into resistant cells called spores. These can survive for long periods on hands, surfaces (such as toilets), objects and clothing unless they’re thoroughly cleaned, and can infect someone else if they get into their mouth.

Someone with a C. difficile infection is generally considered to be infectious until at least 48 hours after their symptoms have cleared up.

More information about C. difficile is available on the NHS website: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/c-difficile/

* Clostridium difficile infection: Epidemiology, diagnosis and understanding transmission, by JS Martin et al in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology 2016.

**The colonisation experiments were done in mice, which although an excellent model to study human disease, are different from humans.

Funding

This work was supported by Wellcome [098051]; the United Kingdom Medical Research Council [PF451 and MR/K000511/1], the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council [1091097 to SF] and the Victorian government.

Selected websites

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a world-leading centre for research, postgraduate studies and continuing education in public and global health. LSHTM has a strong international presence with 3,000 staff and 4,000 students working in the UK and countries around the world, and an annual research income of £140 million. LSHTM is one of the highest-rated research institutions in the UK, is partnered with two MRC University Units in The Gambia and Uganda, and was named University of the Year in the Times Higher Education Awards 2016. Our mission is to improve health and health equity in the UK and worldwide; working in partnership to achieve excellence in public and global health research, education and translation of knowledge into policy and practice. http://www.lshtm.ac.uk

The Wellcome Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute is a world-leading genomics research centre. We undertake large-scale research that forms the foundations of knowledge in biology and medicine. We are open and collaborative; our data, results, tools and technologies are shared across the globe to advance science. Our ambition is vast – we take on projects that are not possible anywhere else. We use the power of genome sequencing to understand and harness the information in DNA. Funded by Wellcome, we have the freedom and support to push the boundaries of genomics. Our findings are used to improve health and to understand life on Earth. Find out more at www.sanger.ac.uk or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and on our Blog.

About Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health by helping great ideas to thrive. We support researchers, we take on big health challenges, we campaign for better science, and we help everyone get involved with science and health research. We are a politically and financially independent foundation. wellcome.org