Out of Africa via Egypt

New research suggests that European and Asian (Eurasian) peoples originated when early Africans moved north – through the region that is now Egypt – to expand into the rest of the world. The findings, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, answer a long-standing question as to whether early humans emerged from Africa by a route via Egypt, or via Ethiopia.

The extensive public catalogue of the genetic diversity in Ethiopian and Egyptian populations developed for the project also now provides a valuable, freely available, reference panel for future medical and anthropological studies in these areas.

Two geographically plausible routes have been proposed for humans to emerge from Africa: through the current Egypt and Sinai (Northern Route), or through Ethiopia, the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Arabian Peninsula (Southern Route). Some lines of evidence have previously favoured one, some the other.

“The most exciting consequence of our results is that we draw back the veil that has been hiding an episode in the history of all Eurasians, improving the understanding of billions of people of their evolutionary history. It is exciting that, in our genomic era, the DNA of living people allows us to explore and understand events as ancient as 60,000 years ago.”

Dr Luca Pagani First author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and University of Cambridge

The team produced whole-genome sequences from 225 people from modern Egypt and Ethiopia. In previous studies, they and others have shown that these modern populations have been subject to gene flow from West Asian populations, so they excluded the Eurasian contribution to the genomes of the modern African people.

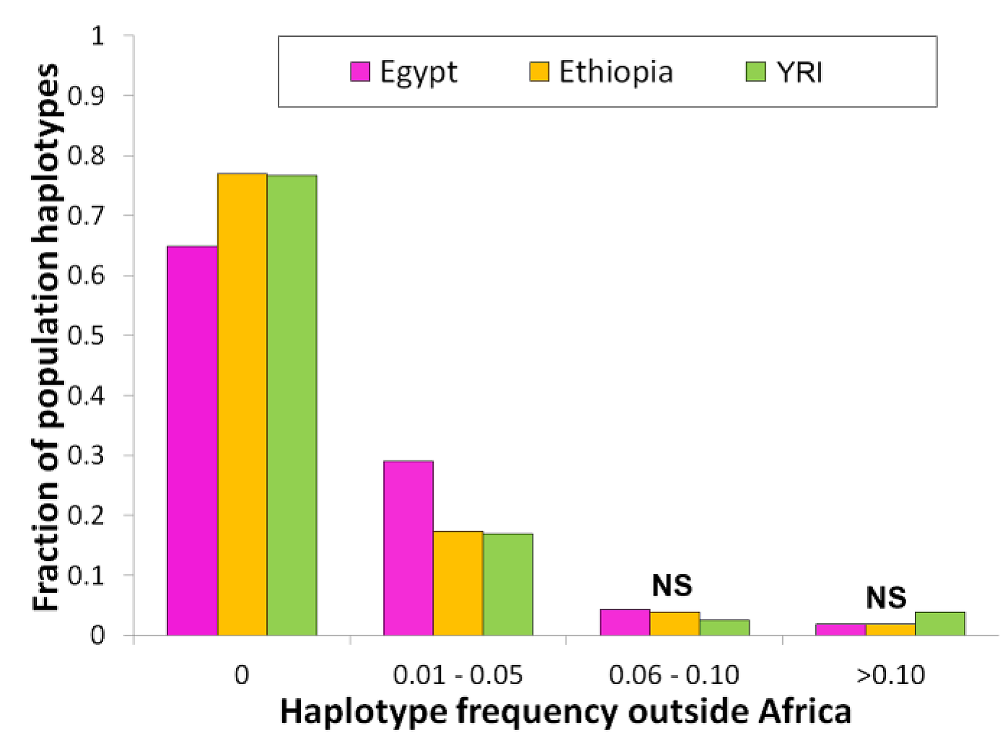

The remaining masked genomic regions from Egyptian samples were more similar to non-African samples and present in higher frequencies outside Africa than the masked Ethiopian genomic regions, pointing to Egypt as the more likely gateway in the exodus to the rest of the world.

The team also used high-quality genomes to estimate the time that the populations split from one another: people outside Africa split from the Egyptian genomes more recently than from the Ethiopians (55,000 as opposed to 65, 000 years ago), supporting the idea that Egypt was last stop on the route out of Africa.

“While our results do not address controversies about the timing and possible complexities of the expansion out of Africa, they paint a clear picture in which the main migration out of Africa followed a Northern, rather than a Southern route.”

Dr Toomas Kivisild A senior author from the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge

The Northern Route as the preferential direction taken out of Africa is in better agreement with the known genetic mixture of all non-Africans with Neanderthals, who were present in the Levant at the time, and with the recent discovery of early modern human fossils in Israel (close to the Northern Route) dating to around 55,000 years ago.

“This important study still leaves questions to answer. For example, did other migrations also leave Africa around this time, but leave no trace in present-day genomes? To answer this, we need ancient genomes from populations along the possible routes. Similarly, by adding present-day genomes from Oceania, we can discover whether or not there was a separate, perhaps Southern, migration to these regions.

“Our approach shows how it is possible to use the latest genomic data and tools to answer these intriguing questions of our human origins and migrations.”

Dr Chris Tyler-Smith A senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

More information

Funding

This research was funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant No. 098051), by an ERC Starting Investigator grant (Grant No. FP7 – 261213) and by an ERC Advanced grant (Grant No. FP7-295733).

Participating Centres

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK

- Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, UK

- Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences, University of Bologna; Italy

- Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, UK

- The Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

- Department of Genetics, Evolution & Environment, University College London, UK

- Henry Stewart Group, London UK

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.