Exploring a parasitic tunnel-boring machine

Researchers have deduced essential biological and genetic information from the genome sequence of the whipworm, an intestinal parasitic worm that infects hundreds of millions of people in developing countries. This information acts as the foundation for the development of new strategies and treatments against this debilitating parasite.

The whipworm is one of three types of soil-transmitted parasitic worms that collectively infect nearly two billion people. While infections often result in mild disease they may also lead to serious and long-term damage such as malnutrition, stunted growth and impaired learning ability. The full extent of worm-associated morbidity and the effect it has on socio-economic development in endemic countries is unknown.

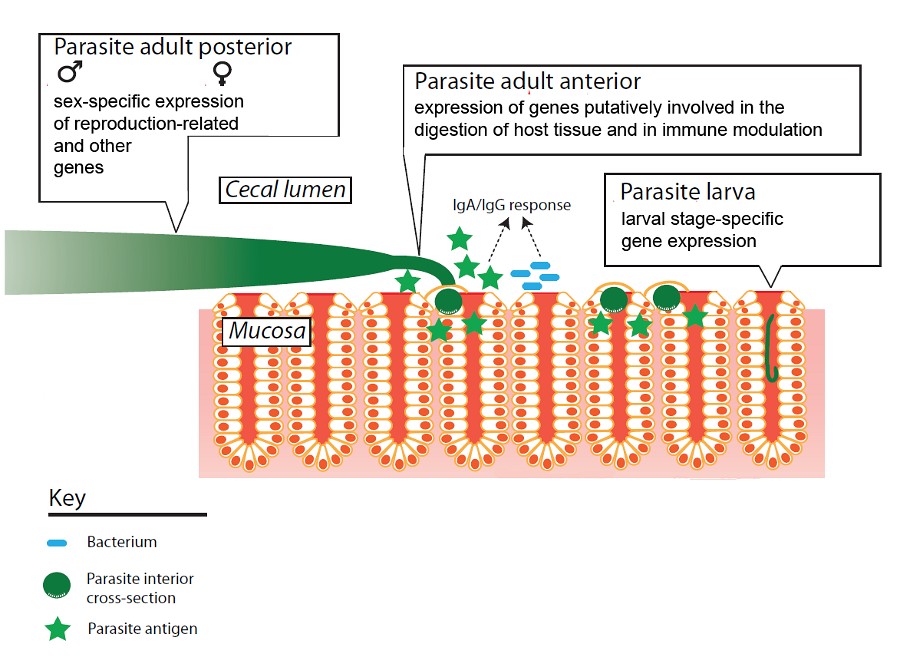

This unusual parasite bores miniature tunnels through the lining of the large intestine where it may live for years. The study has identified molecules that the parasite uses for tunnelling, how the parasite limits the damage it inflicts, and how the immune system responds to infection.

“Worm infections are an enormous public health problem across the Developing World and with so few effective drugs, the emergence of drug resistance is an ever present risk. Our work starts to unravel the whipworm’s intimate relationship with humans and paves the way for new approaches to prevent or clear whipworm infections.

“Making these genome sequences freely available will provide an enormous boost to the entire research community that is working on interventions to prevent or treat worm-associated disease.”

Dr Matthew Berriman Senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The team sequenced the genome of both a human- and a mouse-infective form of the whipworm and examined the genes that are most active and may be essential for its survival. Equipped with this information, the team mined for drug targets that could be used against the whipworm and potentially other parasitic worms.

The genome sequence and the range of proteins the whipworm produces provides a biological understanding of the extraordinary niche this worm has evolved to live in. The team found specific digestive enzymes secreted by the whipworm may burrow through the cells in the gut wall. Other enzymes secreted by the parasite seem to contain the ‘collateral damage’ caused by these digestive enzymes to reduce inflammation and damage to the host’s cells.

“In my experience working with children in Ecuador, these parasites, particularly when present in large numbers in an individual, can have profound effects on health. With more than 800 million children worldwide in need of treatment against these particular worms, and because we have only one or two drugs that are safe and effective against these parasites, it is essential that we focus our research on finding new treatments before resistance to the drugs we have has a chance to develop.

“This study not only opens doors for the development of new drugs but also may allow us to identify already existing drugs used for other diseases that might be effective against this parasite and other types of worms.

“Getting to grips with the genomes and the underlying biology of parasitic worms such as the whipworm is our best option to tackle this growing global problem.”

Professor Philip Cooper Author and clinician from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Whipworm eggs are currently being tested in clinical trials as a treatment against various autoimmune diseases, as it is thought that worm infections may reduce the inflammation associated with disorders such as multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. To determine how the immune system responds to infection, mice were exposed to the mouse-specific type of whipworm. The researchers found that infection caused changes to the activity of many mouse genes that have been associated with inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis.

“Although whipworms can be detrimental to human health and economic growth in some regions, they are also important in defining our immune system’s ‘set point’ and ensuring we make the right level of immune response during disease. The present study shows how both the parasite and the host respond to each other at a level of detail never seen before, that will help us identify how to exploit the ways in which the worm modifies our bodies.

“This finely tuned interaction that has developed over the course of evolution can lead us to design better drug treatments and more effective clinical trials using worms and their products.”

Professor Richard Grencis Senior author from The University of Manchester

More information

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust through their support of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant 098051) and an Investigator Award (WT100290MA) and a Programme grant (WT083620MA) to RKG.

Participating Centres

A full list of participating centres can be found on the paper.

Publications:

Selected websites

The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) has been engaged in the fight against infectious, debilitating and disabling diseases since 1898 and continues that tradition today with a research portfolio in excess of well over £200 million and a teaching programme attracting students from over 65 countries.

The University of Manchester

The University of Manchester, a member of the prestigious Russell Group of British universities, is the largest and most popular university in the UK. It has 20 academic schools and hundreds of specialist research groups undertaking pioneering multi-disciplinary teaching and research of worldwide significance. According to the results of the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise, The University of Manchester is one of the country’s major research institutions, rated third in the UK in terms of ‘research power’, and has had no fewer than 25 Nobel laureates either work or study there. The University had an annual income of £807 million in 2011/12.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.