C'est difficile

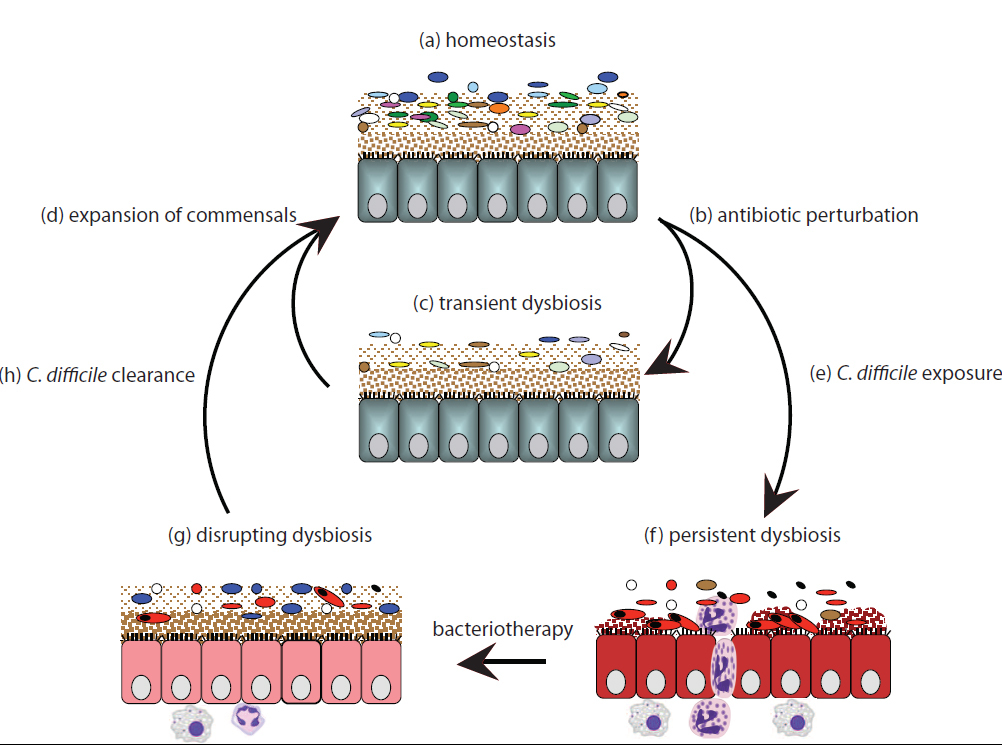

In a new study out today, researchers used mice to identify a combination six naturally occurring bacteria that eradicate a highly contagious form of Clostridium difficile, an infectious bacterium associated with many hospital deaths. Three of the six bacteria have not been described before. This work may have significant implications for future control and treatment approaches.

The researchers found that this strain of C. difficile, known as O27, establishes a persistent, prolonged contagious period, known as supershedding that is very difficult to treat with antibiotics. These contagious ‘supershedders’ release highly resistant spores for a prolonged period that are very difficult to eradicate from the environment. Similar scenarios are likely in hospitals.

C. difficile can cause bloating, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and is a contributing factor to over 2,000 deaths in the UK in 2011. It lives naturally in the body of some people where other bacteria in the gut suppress its numbers and prevent it from spreading. If a person has been treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic such as clindamycin, our bodies’ natural bacteria can be destroyed and the gut can become overrun by C. difficile. The aggressive strain of C. diff analysed in this study has been responsible for epidemics in Europe, North America and Australia.

“We treated mice infected with this persistent form of C. diff with a range of antibiotics but they consistently relapsed to a high level of shedding or contagiousness. We then attempted treating the mice using faecal transplantation, homogenized faeces from a healthy mouse. This quickly and effectively supressed the disease and supershedding state with no reoccurrence in the vast majority of cases.

“This epidemic caused by C. diff is refractory to antibiotic treatment but can be supressed by faecal transplantation, resolving symptoms of disease and contagiousness.”

Dr Trevor Lawley First author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The team wanted to take this research one step further and isolate the precise bacteria that supressed C. diff and restored microbial balance of the gut. They cultured a large number of bacteria naturally found in the gut of mice, all from one of four main groups of bacteria found in mammals. They tested many combinations of these bacteria, until they isolated a cocktail of six that worked best to suppress the infection.

“The mixture of six bacterial species effectively and reproducibly suppressed the C. difficile supershedder state in mice, restoring the healthy bacterial diversity of the gut.”

Professor Harry Flint Senior author from the University of Aberdeen

The team then sequenced the genomes of the six bacteria and compared their genetic family tree to more precisely define them. Based on this analysis, the team found that the mixture of six bacteria contained three that have been previously described and three novel species. This mix is genetically diverse and comes from all four main groups of bacteria found in mammals.

These results illustrate the effectiveness of displacing C. diff and the supershedder microbiota with a defined mix of bacteria, naturally found in the gut.

“Our results open the way to reduce the over-use of antibiotic treatment and harness the potential of naturally occurring microbial communities to treat C. difficile infection and transmission, and potentially other diseases associated with microbial imbalances. Faecal transplantation is viewed as an alternative treatment but it is not widely used because of the risk of introducing harmful pathogens as well as general patient aversion. This model encapsulates some of the features of faecal therapy and acts as a basis to develop standardized treatment mixture.”

Professor Gordon Dougan Senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

More information

Funding

This project was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council.

Participating Centres

- Bacterial Pathogenesis Laboratory, Microbial Pathogenesis Laboratory, Pathogen Genomics and Mouse Genomics, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK

- Microbial Ecology Group, Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB21 9SB, UK

- Departments of Infectious and Tropical Diseases and Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, WC1E 7HT, UK

Publications:

Selected websites

Medical Research Council

For almost 100 years the Medical Research Council has improved the health of people in the UK and around the world by supporting the highest quality science. The MRC invests in world-class scientists. It has produced 29 Nobel Prize winners and sustains a flourishing environment for internationally recognised research. The MRC focuses on making an impact and provides the financial muscle and scientific expertise behind medical breakthroughs, including one of the first antibiotics penicillin, the structure of DNA and the lethal link between smoking and cancer. Today MRC funded scientists tackle research into the major health challenges of the 21st century.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is one of the world’s leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.