Diabetes drug boosts survival rate for melioidosis patients

Scientists have shown that a drug used to treat diabetes halves the mortality rate of melioidosis, a deadly infectious disease found in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. The results lay the foundation for the development of new, related drugs, which could use similar mechanisms to treat melioidosis and other infectious diseases in the future.

The team found that when patients with melioidosis are treated with the diabetes drug glibenclamide – also known as glyburide in the US – they are half as likely to die from the disease. The research suggests that the drug reduces excessive inflammation, or sepsis, in patients responding to infection.

Melioidosis is caused by a soil dwelling bacterium called Burkholderia pseudomallei. In endemic areas, the bacterium can invade the patients’ bloodstream causing lung and other organ infections and, in some cases, whole body inflammation, known as bacterial sepsis. Even with antibiotic treatment, up to 40 per cent of people die from the disease. Patients with diabetes are twice as likely to contract the disease.

“Roughly half of all patients with melioidosis have diabetes as a risk factor. Our Thai collaborators realised several years ago that diabetics are more likely to get melioidosis, but are less likely to die from their infection compared with non-diabetics. Our research shows that this improvement in survival is not an effect of diabetes itself, but of glibenclamide which is often prescribed to control the high blood sugar of diabetes.”

Dr Gavin Koh an infectious diseases doctor at the University of Cambridge and first author of the study

The researchers looked at almost 1200 patients with melioidosis in northeast Thailand, including more than 400 diagnosed diabetics. They found that less than 30 per cent of patients taking glibenclamide to treat their diabetes die from melioidosis infection. By contrast, the mortality rate in diabetic patients receiving treatment with other drugs and the non-diabetic group was almost twice that figure.

“Glibenclamide cannot be given safely to people who present to hospital with severe bacterial infection who are not diabetic. But we hope that our findings will result in further research to define the mechanisms by which the drug increases patient survival, and to the development of related drugs that share these mechanisms but that do not lower blood sugar levels and can be given safely to all patients with severe sepsis.”

Sharon Peacock Professor of Clinical Microbiology in the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge, Honorary Faculty member at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and senior author on the study

To begin to understand the mechanisms by which glibenclamide boosts survival in patients, the researchers asked whether the drug might be attacking the Burkholderia pseudomallei bacteria directly. However, when they looked at the effect of the drug on the bacteria, outside the patient, they found little evidence that its constituents were hindering the success or survival of the bug.

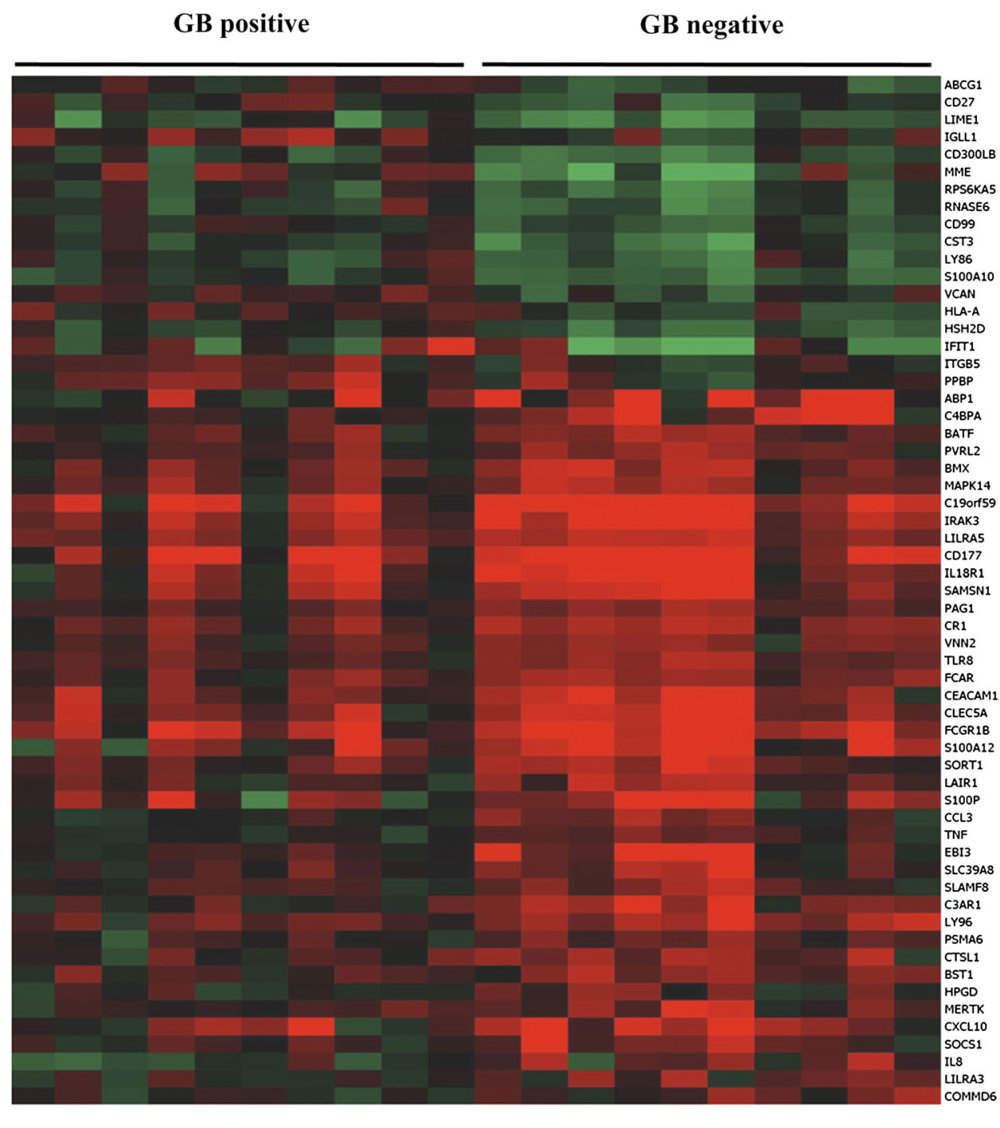

To try to pinpoint other ways in which the drug might help patients survive the disease, the team looked at how the activity of genes in ten diabetic patients taking glibenclamide compared with the activity of genes in ten diabetic patients who were not taking the drug.

The comparison exposed more than 60 immune-related genes that behaved differently between the two groups. The lineup included genes that are responsible for activating a group of white blood cells – known as neutrophils – which travel through the bloodstream to the area of inflammation during infection. Other possible culprits activate a group of molecules that line the inside of blood vessels, delivering neutrophils to the site of inflammation.

“This is a practical example of how genomics can be used to directly help clinical practice. Here we were able to identify previously unidentified target cells for a well-known drug as well as identify a new use.”

Professor Gordon Dougan from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and an author on the paper

The results suggest that glibenclamide is likely to constrain the immune response to melioidosis and support the theory that excessive inflammation contributes to death rates for melioidosis and other similar bacterial diseases.

By revealing new mechanisms by which glibenclamide can boost patient survival, the team opens the door for studies dedicated to delivering new, related drugs that can be used in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients to alleviate the burden of melioidosis and other pathogenic infections.

More information

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

Participating Centres

- Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- Department of Infection and Tropical Medicine, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford, Churchill Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom

- Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok

- Department of Medicine, Sappasithiprasong Hospital, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand

- Center for Infection and Immunity Amsterdam (CINIMA) and Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine (CEMM), Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.