Broken genomes behind breast cancers

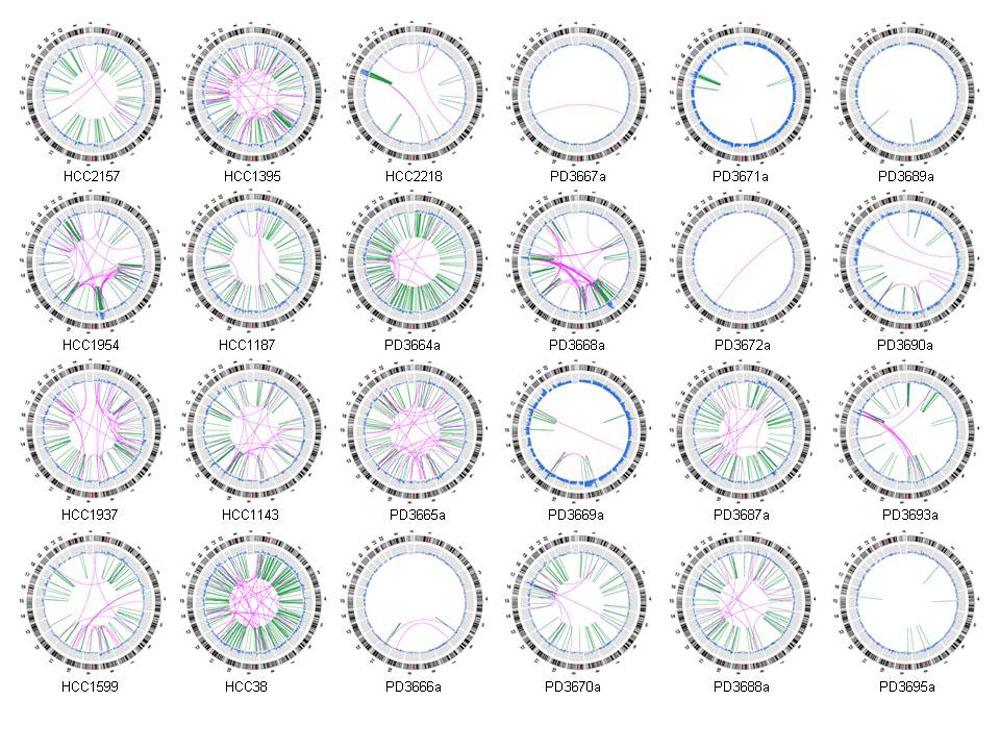

The first detailed search of breast cancer genomes to uncover genomic rearrangements is published today. The team characterised the ways in which the human genome is broken and put back together in 24 cases of breast cancer.

Rearrangements involve reshuffling and reorganisation of the genome and include deletions, duplications and novel juxtaposition of DNA sequences. The study shows that breast cancer samples can differ greatly in the extent to which they are subject to genomic rearrangements: some are relatively undisturbed whereas others are fractured extensively and then reassembled with more than 200 rearrangements present.

While it is known that the majority of cancer genes important in blood cancers are activated by rearrangement, the role of this process in the common adult cancers is much less clear. This new study builds on pioneering work from the team using next-generation sequencing to characterise comprehensively rearrangements in adult solid tumours.

“We have looked at the level of the DNA sequence at just how splintered and reorganised the genome is in many breast cancers. We were, frankly, astounded at the number and complexity of rearrangements in some cancers. Just as important, the genomes were different from each other, with multiple distinctive patterns of rearrangement observed, supporting the view that breast cancer is not one, but several diseases.”

Professor Mike Stratton of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The information obtained from this study will add a new dimension to tumour classification and thus refine diagnosis and treatment.

In the study The team used next-generation DNA sequencing to produce maps of genome rearrangements in 24 breast cancer samples, which were chosen to include the major subtypes of breast cancer and also included examples of breast cancers arising in BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer families.

One breast cancer showed just a single genomic rearrangement – while others showed more than 200. The study provides detailed insights into the ways that the genome in some cancers have broken and also the processes that were used by the cancer cell in gluing the broken bits of genome back together again.

“It looks as though some breast cancers have a defect in the machinery that maintains and repairs DNA and this defect is resulting in large numbers of these abnormalities. At the moment we do not know what the defect is or the abnormal gene underlying it, but we are seeing the result of its malfunction in the hideously untidy state of these genomes. Identifying the underlying mutated cause will be central to working out how some breast cancers develop.”

Dr Andy Futreal of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The broad groups of rearrangement were associated with different subtypes of breast cancer: HER2 positive breast cancers – those that are responsive to herceptin – have similar patterns of disruption. By the same measure, triple-negative breast cancers, which don’t respond to treatment with herceptin or hormones, looked similar.

The size of the DNA regions that are deleted, duplicated or removed ranges from a few hundred letters of DNA code to several millions. Most changes were rearrangements within the same chromosome, but there were also a substantial number involving the joining of two different chromosomes.

Dissecting out the complexity and the diversity of the breast cancer genomes is important for understanding how the cancers arise. Importantly, however, the apparent loss of DNA repair systems raises the possibility of new therapeutic opportunities in some breast cancers.

“It appears that in different subtypes of breast cancers, distinct mechanisms of DNA repair are impaired, leading to different types of genomic disorganisation.

“If we damage further an already-faulty DNA repair system using tailored therapies, one can kill tumour cells selectively, without harming normal cells. There are already some highly interesting results suggesting that breast cancers with defects in DNA repair are more sensitive to drugs that cause additional DNA damage.”

Dr Jorge Reis-Filho Team leader from the Breakthrough Breast Cancer Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research

More information

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Human Frontiers, the Dana-Farber/Harvard SPORE in breast cancer, Breakthrough Breast Cancer, the Research Council of Norway

Participating Centres

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK

- Molecular Pathology Laboratory, The Breakthrough Breast Cancer Research Centre, Institute of Cancer Research, London SW3 6JB, UK

- Dept. Medical Oncology, Josephine Nefkens Institute and Cancer Genomics Centre, Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

- Department of Genetics, Institute for Cancer Research, Norwegian Radium Hospital, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

- The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston MA, USA

- Faculty Division, The Norwegian Radium Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

- Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton, Surrey, UK

Publications:

Selected websites

Breakthrough Breast Cancer

Breakthrough Breast Cancer funds ground-breaking research, campaigns for better services and treatments and raises awareness of breast cancer. Through this work the charity believes passionately that breast cancer can be beaten and the fear of the disease removed for good. Under the directorship of Professor Alan Ashworth FRS, the Breakthrough Research Centre now has 120 world-class scientists and clinicians tackling breast cancer from all angles – from understanding the normal growth and development of the breast, how breast cancer arises and how the cancer spreads, to treatment and ultimately disease prevention. Scientists at the Breakthrough Research Centre have a range of expertise and approaches and together they are working towards a common goal: a future free from the fear of breast cancer.

The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR)

- The ICR is Europe’s leading cancer research centre

- The ICR has been ranked the UK’s top academic research centre, based on the results of the Higher Education Funding Council’s Research Assessment Exercise

- The ICR works closely with partner The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust to ensure patients immediately benefit from new research. Together the two organisations form the largest comprehensive cancer centre in Europe

- The ICR has charitable status and relies on voluntary income, spending 95 pence in every pound of total income directly on research

- As a college of the University of London, the ICR also provides postgraduate higher education of international distinction

- Over its 100-year history, the ICR’s achievements include identifying the potential link between smoking and lung cancer which was subsequently confirmed, discovering that DNA damage is the basic cause of cancer and isolating more cancer-related genes than any other organisation in the world

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.