Genetic study of malaria

A study of children with malaria in The Gambia, West Africa, has provided new insights into how to conduct genetic studies of common diseases in African populations, which are far more genetically-diverse than European or Asian populations.

The study was carried out by MalariaGEN, a global network of malaria researchers, who are trying to understand why some people die from malaria while others survive despite repeated malaria infections.

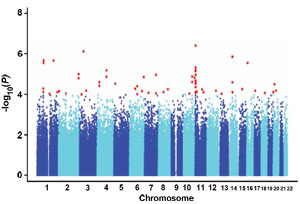

Scientists believe that a wide range of genetic factors affect an individual’s ability to resist malaria, and MalariaGEN researchers are attempting to discover these by genome-wide association (GWA) studies. This involves looking at hundreds of thousands of points in the genome that might vary between individuals, comparing people who are affected by the disease with the general population.

“GWA studies have been highly successful in discovering regions of the genome that affect susceptibility to common diseases in European populations, but there are considerable challenges in applying this approach to African populations. That is because there is much more genetic diversity in Africa than in other parts of the world.”

Professor Dominic Kwiatkowski from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, who is leading the project

Now, in a paper published online in Nature Genetics on Sunday, Professor Kwiatkowski and colleagues have demonstrated a way forward for GWA studies in Africa. The researchers carried out a GWA study of thousands of Gambian children, in search of genetic variants associated with resistance to fatal forms of malaria.

After examining the whole genome they focused on the specific region that contains the sickle cell haemoglobin variant, which is known to be a remarkably strong protective factor against malaria: children carrying one copy of this variant have ten-fold reduced risk of fatal forms of malaria than those who do not carry the variant.

Using a computational method known as imputation, they combined the GWA data with DNA sequencing data from the Gambian population, and found that they could easily detect the malaria-protective effect of the sickle variant. In fact they were able to go further than this, and to pinpoint the precise spot in the genome where this malaria-protective factor is located.

Professor Kwiatkowski believes that this method is the key to genetic studies of common diseases in African populations, which may ultimately reveal more than similar studies on other populations.

“In European and Asian populations, GWA studies can identify regions of the genome where disease resistance and susceptibility factors are located, but pinpointing the exact causal variant within these regions is proving very difficult. In African populations, it is the other way round: it is harder work to discover important regions of the genome but, once they have been found, it may be easier to locate the exact causal variant.”

Professor Dominic Kwiatkowski Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

MalariaGEN (www.malariagen.net) was established in 2005 with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as part of the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative.

More information

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health as part of the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative and the Medical Research Council

Websites

- MalariaGEN – http://www.malariagen.net/

Participating Centres

- MRC Laboratories, Atlantic Road, Fajara, Banjul, Gambia.

- Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK.

- Department of Statistics, Oxford University, Oxford, UK.

- Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme, College of Medicine, University of Malawi, Chichiri, Blantyre, Malawi.

- The University of Buea, Buea, South West Province, Cameroon.

- Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Private Mail Bag, Kumasi, Ghana.

- Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, Madang, Papua New Guinea.

- Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- Institute of Child Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

- National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, Hertfordshire, UK.

- The Malaria Research & Training Centre, University of Bamako, Bamako, Mali.

- London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK.

- Joint Malaria Programme, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Tanzania.

- Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, The Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

- Department of Molecular Medicine, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany.

- Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Institute for Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Medical Service Science Campus, PO Box 102, Khartoum, Sudan.

- Kenyan Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Wellcome Trust Programme, Kilifi, Kenya.

- Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana.

- National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Rome, Italy.

- The Ethox Centre, Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care, University of Oxford, Headington, Oxford, UK.

- Blantyre Malaria Project, Chichiri, Blantyre 3, Malawi.

- Howard Hughes Medical Institute/University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

- Institut Pasteur, Unité d’Immunologie Moléculaire des Parasites, Paris, France.

- Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Ratchathewi, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Centre National de Recherche et Formation sur le Paludisme, Avenue de l’Oubritenga, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

- lnstitut Pasteur de Dakar, Dakar, Senegal.

- Michigan State University, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Osteopathic Medicine, East Lansing, Michigan, USA.

- The Wenner-Gren Institute, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.

The Wellcome Trust

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. We support the brightest minds in biomedical research and the medical humanities. Our breadth of support includes public engagement, education and the application of research to improve health. We are independent of both political and commercial interests.