The cryptic past of Madagascar

The island of Madagascar, the largest in the Indian Ocean, lies some 250 miles (400 km) from Africa and 4000 miles (6400 km) from Indonesia. Its isolation means that most of its mammals, half of its birds, and most of its plants exist nowhere else on earth. The new findings, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, show that the human inhabitants of Madagascar are similarly unique – amazingly, half of their genetic lineages derive from settlers from the region of Borneo, with the other half from East Africa. Archaeological evidence suggests that this settlement was as recent as 1500 years ago – about the time the Saxons invaded Britain.

“The origins of the language spoken in Madagascar, Malagasy, suggested Indonesian connections, because its closest relative is the Maanyan language, spoken in southern Borneo. For the first time, we have been able to assign every genetic lineage in the Malagasy population to a likely geographic origin with a high degree of confidence.”

“Malagasy peoples are a roughly 50:50 mix of two ancestral groups: Indonesians and East Africans. It is important to realise that these lineages have intermingled over intervening centuries since settlement, so modern Malagasy have ancestry in both Indonesia and Africa.”

Dr Matthew Hurles Of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

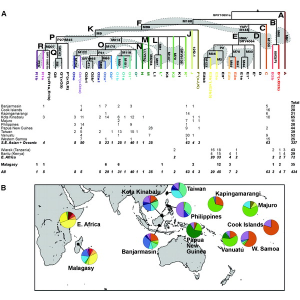

The team, from Cambridge, Oxford and Leicester, used two types of DNA marker to study DNA diversity: Y chromosomes, inherited only through males, and mitochondrial DNA, inherited only through females. They tested how similar the Malagasy were to populations around the Indian Ocean. The set of non-African Y chromosomes found in the Malagasy was much more similar to the set of lineages found in Borneo than in any other population, which demonstrates striking agreement between the genetic and linguistic evidence. Similarly, a ‘Centre of Gravity’ was estimated for every mitochondrial DNA to suggest a likely geographical origin for each. This entails calculating a geographical average of the locations of the best matches within a large database of mitochondrial lineages from around the world.

“The Centres of Gravity fell in the islands of southeast Asia or in sub-Saharan Africa. The evidence from these two independent bits of DNA supports the linguistic evidence in suggesting that a migrating population made their way 4500 miles across the Indian Ocean from Borneo.”

Dr Peter Forster From the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge

The striking mix suggests that there was substantial migration of people from southeast Asia about 2000-1500 years ago – a mirror image of the migrations from that region into the Pacific, to Micronesia and Polynesia, that had occurred about 1000 years earlier. However, unlike the privations suffered by those eastward travellers, the data suggests the early Malagasy population survived the voyage well, because more genetic variation is found in them than is found in the islands of Polynesia. ‘Bottlenecks’ in evolutionary history, where the population is dramatically reduced in number, are a common cause of reduced genetic variation.

Even though the Africa coast is only one-twentieth of the distance to Indonesia, it appears that migrations from Africa may have been more limited, as less of the diversity seen in the source population has survived in Madagascar.

But why, if the population is a 50:50 mix, is the language almost exclusively derived from Indonesia?

“It is a very interesting question, for which we have as yet no certain answer, as to how the African contribution to Malagasy culture, evident in biology and in aspects of economic and material culture, was so largely erased in the realm of language. This research highlights the differing, and complementary, contributions of biology and linguistics to the understanding of prehistory.”

Professor Robert Dewar Of The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge

The population structure in Madagascar is a fascinating snapshot of human history and a testament to the remarkable abilities of early populations to undertake migrations across vast reaches of ocean. It may also be important today for cutting edge medical science.

“There has recently been dramatic progress in the development of experimental and statistical methods appropriate for gene mapping in admixed populations. To succeed, however, these methods depend on populations with well defined historical admixtures. This work shows provides compelling evidence that the Malagasy are such a population, and again shows the value of careful study of human population structure.”

David Goldstein Wolfson Professor of Genetics, University College London

Our human history is a rich mix of peoples and their movement, of success and failure. Madagascar holds an enriching tale of the ability of humans to survive and to reach new lands.

More information

Participating Centres

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute – Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK

- McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research – University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

- Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine – University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- Department of Genetics – University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Publications:

Selected websites

The Wellcome Trust and Its Founder

The Wellcome Trust is the most diverse biomedical research charity in the world, spending about £450 million every year both in the UK and internationally to support and promote research that will improve the health of humans and animals. The Trust was established under the will of Sir Henry Wellcome, and is funded from a private endowment, which is managed with long-term stability and growth in mind.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which receives the majority of its funding from the Wellcome Trust, was founded in 1992. The Institute is responsible for the completion of the sequence of approximately one-third of the human genome as well as genomes of model organisms and more than 90 pathogen genomes. In October 2006, new funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust to exploit the wealth of genome data now available to answer important questions about health and disease.