Hidden genetic effects behind immune diseases may be missed, study suggests

The results, published today (29 January) in Nature Genetics, show for the first time how immune cells created from human induced pluripotent stem cells (HiPSCs) can model immune response variation between people.

Researchers discovered that the differences in immune responses due to genetic variation were only visible at certain stages of the experiment when the immune cells were in particular states, for example when they were activated.

In other states, only ‘footprints’ of the genetic variation effects could be seen. However by looking at two elements, the genes and regulatory regions – the molecular ‘switches’ that control the expression of those genes, the researchers were able to identify the true impact of genetic differences on immune response.

The results suggest that the actual effects of genetic variation on immune response are often hidden if not searched for thoroughly.

An understanding of the role genetic variants play in helping our immune systems fight diseases is an important step towards better targeted therapies.

“We have found that the impact of genetic variants on how people’s immune cells respond to a pathogen like Salmonella are condition-specific – they are only visible at certain stages of infection. This means that the effects of genetic differences in immune disorders could be missed in research, if scientists aren’t studying both the genes and their control regions, the regulatory elements, of immune cells at all stages of an infection.”

Dr Daniel Gaffney Group Leader and senior author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

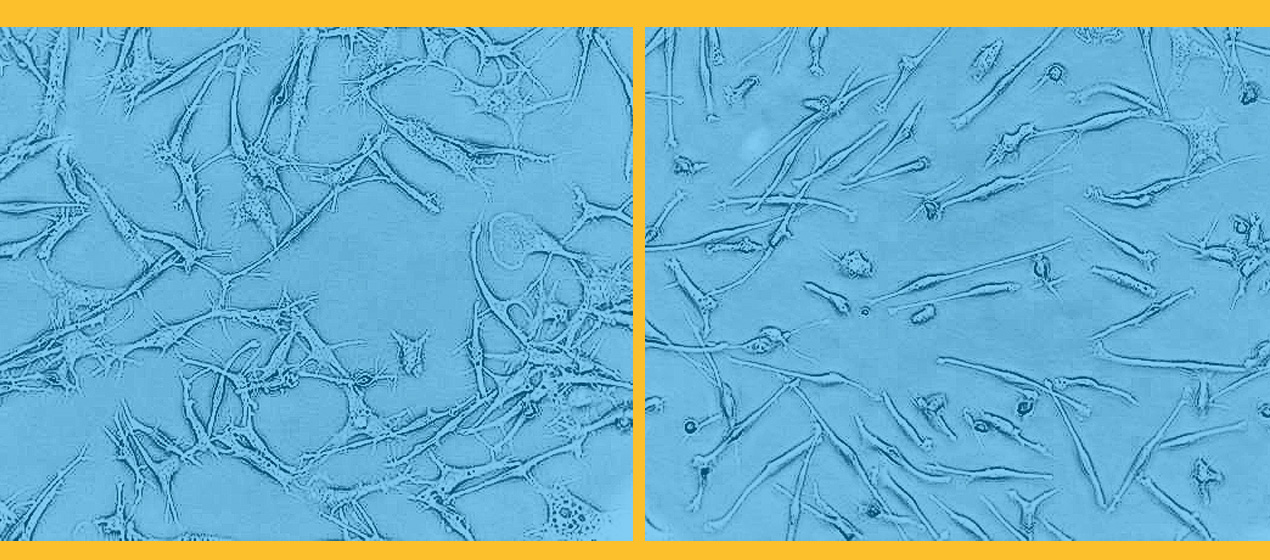

In the study, scientists differentiated human induced pluripotent stem cells* into white blood cells called macrophages. The macrophages were then studied in four different states:

- unstimulated,

- after 18 hours of stimulation with a signalling molecule interferon-gamma,

- after five hours infection with Salmonella,

- and after interferon-gamma stimulation followed by Salmonella infection.

“A benefit of using stem cells rather than pre-existing blood cells is they’re very flexible, and enabled us to study the effects of stimulation at two different levels. We analysed which genes in the genome were expressed during each stage of infection, but also looked at the activity of enhancers – the molecular ‘switches’ that controlled the expression of those genes. This novel combination of tools enabled us to see otherwise hidden effects of genetic variation on immune response.”

Dr Kaur Alasoo Previously from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and now based at the University of Tartu, Estonia

The team also discovered that genetic variation impacts on the readiness of the immune cells to tackle an infection. In particular, some individuals’ immune cells were ready to deal with the Salmonella infection, whereas other individuals’ macrophages were less ready and took longer to respond. This level of ‘readiness’ was due to a phenomenon known as enhancer priming, where some of the switches were already turned on in the unstimulated cells to facilitate a quicker response. In some cases, the immune cells could be overly eager and this can lead to an inflammatory response associated with immune disorders.

“If the genetic variant being studied is associated with disease, such as an immune disorder, one needs to be sure of which gene the variant is affecting in order to develop an effective therapy. This may only be visible in a small time-window of the infection. These results offer important new insights into studying the mechanisms behind infection and disease.”

Professor Gordon Dougan Group Leader from the Wellcome Sanger Institute

More information

*The human induced pluripotent stem cells were obtained from the HipSci initiative. HipSci brings together diverse constituents in genomics, proteomics, cell biology and clinical genetics to create a global induced pluripotent stem cell resource for the research community. http://www.hipsci.org/

Funding

This work was supported by Wellcome (grant WT 098051).

Publications:

Selected websites

University of Tartu

University of Tartu, founded in 1632, is the leading centre of research and training in Estonia. UT belongs to the top 1.2% of world's best universities. The robust research potential of the university is evidenced by the fact that the University of Tartu has been invited to join the Coimbra Group, a prestigious club of renowned research universities. http://www.ut.ee

HipSci

The HipSci initiative brings together diverse constituents in genomics, proteomics, cell biology and clinical genetics to create a global induced pluripotent stem cell resource for the research community. http://www.hipsci.org/

The Wellcome Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute is one of the world's leading genome centres. Through its ability to conduct research at scale, it is able to engage in bold and long-term exploratory projects that are designed to influence and empower medical science globally. Institute research findings, generated through its own research programmes and through its leading role in international consortia, are being used to develop new diagnostics and treatments for human disease. To celebrate its 25th year in 2018, the Institute is sequencing 25 new genomes of species in the UK. Find out more at scion-02.sandbox.sanger.ac.uk or follow @sangerinstitute

Wellcome

Wellcome exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive. We’re a global charitable foundation, both politically and financially independent. We support scientists and researchers, take on big problems, fuel imaginations and spark debate. wellcome.org